Is Russia’s Presence in Syria the Beginning of the Gog and Magog War?

“The newspaper has no prerogative to challenge God’s word of truth. Nor do those who read the newspapers.”1

With Russia’s recent airstrikes targeting rebels in Syria, this end times subject matter is once again getting some attention, though it remains controversial, as many counter that the Old Testament simply doesn’t offer up any eschatological proclamations about the modern era.

“The Hebrew prophet Ezekiel wrote 2,500 years ago that in the ‘last days’of history, Russia and Iran will form a military alliance to attack Israel from the north,” Rosenberg wrote. “Bible scholars refer to this eschatological conflict, described in Ezekiel 38-39, as the ‘War of Gog & Magog.'”

Not everyone agrees. Keep in mind that there is a long history of prophetic prognosticators who have argued that the events described in Ezekiel 38 and 39 were being fulfilled in their day.

The following is a brief introduction to the topic that interprets Ezekiel 38 and 39 in terms of its historical context.

For a comprehensive treatment of this subject, see my book Why the End of the World is Not in Your Future. It’s a full exposition of Ezekiel 38 and 39 as well as Zechariah 12.

The battle is an ancient one fought with ancient weapons: bows and arrows, clubs, shields, chariots, swords, and chariots. The combatants are on horseback.

Many interpreters will argue that these ancient weapons are only “symbolic.” One prophecy writer claims that bows and arrows are symbols for missile launchers and missiles. This is no way to interpret the Bible. Why confuse the people in Ezekiel’s day and our day?

In Ezekiel 38:13 we read that the enemies of the Jews wanted to “seize plunder, to carry away silver and gold, to take away cattle and goods, to capture great spoil.” In Ezra 1:4, we learn that these are the same items that the Jews brought back from their captivity:

“Every survivor, at whatever place he may live, let the men of that place support him with silver and gold, with goods and cattle, together with a freewill offering for the house of God which is in Jerusalem.”

If the battle described in Ezekiel 38–39 does not refer to modern-day nations that will attack Israel, then when and where in biblical history did this conflict take place? Instead of looking to the distant future or finding fulfillment in a historical setting outside the Bible where we are dependent on unreliable secular sources, James B. Jordan believes that “it is in [the book of] Esther that we see a conspiracy to plunder the Jews, which backfires with the result that the Jews plundered their enemies. This event is then ceremonially sealed with the institution of the annual Feast of Purim.” ((James B. Jordan, Esther in the Midst of Covenant History (Niceville, FL: Biblical Horizons, 1995), 5.)) Jordan continues by establishing the context for Ezekiel 38 and 39:

“Ezekiel describes the attack of Gog, Prince of Magog, and his confederates. Ezekiel states that people from all over the world attack God’s people, who are pictured dwelling at peace in the land. God’s people will completely defeat them, however, and the spoils will be immense. The result is that all nations will see the victory, and ‘the house of Israel will know that I am the Lord their God from that day onward’ (Ezek. 39:21–23). . . .

“Chronologically this all fits very nicely. The events of Esther took place during the reign of Darius, after the initial rebuilding of the Temple under Joshua [the High Priest] and Zerubbabel and shortly before rebuilding of the walls by Nehemiah. . . . Thus, the interpretive hypothesis I am suggesting (until someone shoots it down) is this: Ezekiel 34–37 describes the first return of the exiles under Zerubbabel, and implies the initial rebuilding of the physical Temple. Ezekiel 38–39 describes the attack of Gog (Haman) and his confederates against the Jews. Finally, Ezekiel 40–48 describes in figurative language the situation as a result of the work of Nehemiah.”2

Read more: “The Isaiah 17 Damascus Bible Prophecy has been Fulfilled.”

Ezekiel 38:5–6 tells us that Israel’s enemies come from “Persia, Cush, and . . . from the remote parts of the north,” all within the boundaries of the Persian Empire of Esther’s day. From Esther we learn that the Persian Empire “extended from India to Cush, 127 provinces” in all (Esther 8:9). Ethiopia (Cush) and Persia are listed in Esther 1:1 and 3 and are also found in Ezekiel 38:5. The other nations were in the geographical boundaries “from India to Ethiopia” in the “127 provinces” over which Ahasueras ruled (Esther 1:1). “In other words, the explicit idea that the Jews were attacked by people from all the provinces of Persia is in both passages,”3 and the nations listed by Ezekiel were part of the Persian empire of the prophet’s day.

The parallels are unmistakable. Even Ezekiel’s statement that the fulfillment of the prophecy takes place in a time when there are “unwalled villages” (Ezek. 38:11) is not an indication of a distant future fulfillment as Grant Jeffrey attempts to argue:

“It is interesting to note that during the lifetime of Ezekiel and up until 1900, virtually all of the villages and cities in the Middle East had walls for defense. Ezekiel had never seen a village or city without defensive walls. Yet, in our day, Israel is a ‘land of unwalled villages’ for the simple reason that modern techniques of warfare (bombs and missiles) make city walls irrelevant for defense. This is one more indication that his prophecy refers to our modern generation.

* * * * *

“Ezekiel’s reference to ‘dwell safely’ and ‘without walls . . . neither bars nor gates’ refers precisely to Israel’s current military situation, where she is dwelling safely because of her strong armed defense and where her cities and villages have no walls or defensive bars. The prophet had never seen a city without walls, so he was astonished when he saw, in a vision, Israel dwelling in the future without walls. Ezekiel lived in a time when every city in the world used huge walls for military defense.”4

In the book of Esther we learn that there were Jews who were living peacefully in “unwalled towns” (KJV) (9:19) when Haman conspired against them. Israel’s antagonists in Ezekiel are said to “go up against the land of unwalled villages” (Ezek. 38:11). The Hebrew word perazah is used in Esther 9:19 and Ezekiel 38:11. It’s unfortunate that the translators of the New American Standard Version translate perazah as “rural towns” in Esther 9:19 instead of “unwalled villages” as they do in Ezekiel 38:11.

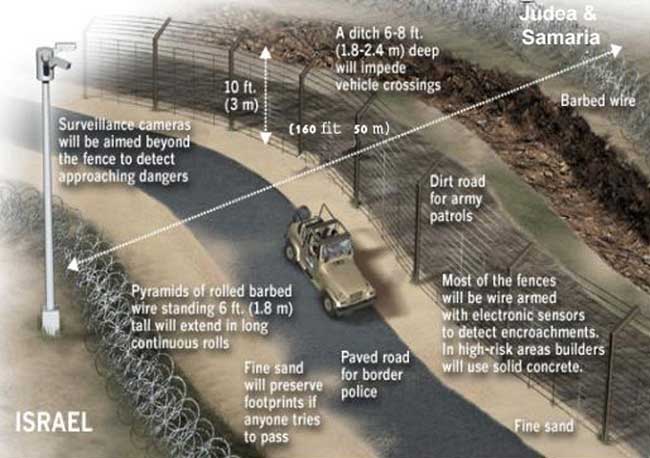

The mention of “unwalled villages” the conditions of Esther’s day. Jeffrey is mistaken in his assertion that “Ezekiel had never seen a village or city without defensive walls.” They seemed to be quite common outside the main cities. Moreover, his contention that Israel is currently “dwelling safely because of her strong armed defense” is patently untrue. Since 2006, the Israeli government has built more than 435 miles of walls, fences, and barriers in Israel.

The chief antagonist of the Jews in Esther is Haman, “the son of Hammedatha the Agagite” (Esther 3:1, 10; 8:3, 5; 9:24).5

An Agagite is a descendant of Amalek, one of the persistent enemies of the people of God. In Numbers 24:20 we read, “Amalek was the first of the nations, but his end shall be destruction.” The phrase “first of the nations” takes us back to the early chapters of Genesis where we find “Gomer,” “Magog,” “Tubal,” and “Meshech,” and their father Japheth (Gen. 10:2), the main antagonist nations that figure prominently in Ezekiel 38 and 39. Amalek was probably a descendant of Japheth (Gen. 10:2). Haman and his ten sons are the last Amalekites who appear in the Bible. In Numbers 24:7, the Septuagint (LXX) translates “Agag” as “Gog.” “One late manuscript to Esther 3:1 and 9:24 refers to Haman as a ‘Gogite.’”6 Agag and Gog are very similar in their Hebrew spelling and meaning. Agagite means “I will overtop,” while Gog means “mountain.” In his technical commentary on Esther, Lewis Bayles Paton writes:

“The only Agag mentioned in the OT is the king of Amalek [Num. 24:7; 1 Sam. 15:9]. . . . [A]ll Jewish, and many Christian comm[entators] think that Haman is meant to be a descendant of this Agag. This view is probably correct, because Mordecai, his rival, is a descendant of Saul ben Kish, who overthrew Agag [1 Sam. 17:8–16], and is specially cursed in the law [Deut. 25:17]. It is, therefore, probably the author’s intention to represent Haman as descended from this race that was characterized by an ancient and unquenchable hatred of Israel (cf. 3:10, ‘the enemy of the Jews’).”7

A cursive Hebrew manuscript identifies Haman as “a Gogite.”8 Paul Haupt sees a relationship between Haman’s descriptions as an Agagite and “the Gogite.” ((Paul Haupt, “Critical Notes on Esther,” OT and Semitic Studies in Memory of W. R. Harper, II (Chicago: 1908), 194–204.))

There is another link between Haman the Agagite in Esther and Gog in Ezekiel 38–39. “According to Ezekiel 39:11 and 15, the place where the army of Gog is buried will be known as the Valley of Hamon-Gog, and according to verse 16, the nearby city will become known as Hamonah.”9 The word hamon in Ezekiel “is spelled in Hebrew almost exactly like the name Haman. . . . In Hebrew, both words have the same ‘triliteral root’ (hmn). Only the vowels are different.”10

Haman is the “prince-in-chief” of a multi-national force that he gathers from the 127 provinces with the initial permission of king Ahasuerus to wipe out his mortal enemy—the Jews (Ex. 17:8–16; Num. 24:7; 1 Sam. 15:8; 1 Chron. 4:42–43; Deut. 25:17–19). Consider these words: “King Ahasuerus promoted Haman, the son of Hammedatha the Agagite, and advanced him and established his authority over all the princes who were with him” (Esther 3:1). Having “authority over all the princes who were with him” makes him the “chief prince.” In Esther 3:12 we read how Haman is described as the leader of the satraps, governors, and princes. The importance of this title is made clear in my book Why the End of the World is Not in Your Future.

As I point out in Why the End of the World is Not in Your Future, when historical circumstances change, there are changes in interpretation. Islam was considered the prophetic Gog as far back as the eighth century. Protestant Reformer Martin Luther (1483–1546) believed that “the papacy was the antichrist alluded to in the eleventh chapter of Daniel, and the Turk was the small horn that replaced three horns of the beast in the seventh chapter.”11 Hal Lindsey began his prophetic career identifying Russia as Gog in his 1970 blockbuster The Late Great Planet Earth but later changed to the Islamic nations.

From Francis X. Gumerlock’s “The Day and the Hour: Christianity’s Perennial Fascination with Prediction the End of the World”

Peter Toon offers a helpful historical perspective on the way commentators understood the place of Islam and the Papacy in relation to Bible prophecy:

“References to the Turkish Empire appear in virtually every Commentary on the Apocalypse of John which was produced by English Puritans, Independents, Presbyterians and Baptists. Gog and Magog were identified with the armies of Turkey and the Muslim world, descriptions of Turkish military power were seen in the contents of the trumpet (Rev. 9:13–21), and the year 1300 was believed to have great significance for it was at that time that the Turk became a threat to European civilization.

* * * * *

“For the English Puritans, as for many of their fellow Protestants on the Continent of Europe, the fact that the Ottoman Empire had for its religion Islam, the teaching of Mohammed, the ‘false’ prophet of God, was sufficient to label it as an envoy or agent of Satan, seeking to destroy the true Church of Christ. In view of this we cannot be surprised to learn that they believed God had given to John on Patmos a vision of this great enemy of the elect of God, who would one day be destroyed by the power of Christ.”12

The Gog-Magog prophecy was fulfilled in the vents of the book of Esther. We should praise God for this ancient fulfillment when God rescued the Jews from almost certain annihilation (Esther 3:6, 13). It’s because of Esther and Mordecai’s faithfulness and God’s special intervention that the Jewish people were rescued and Jesus was born.

- Greg L. Bahnsen, “The Prima Facie Acceptability of Postmillennialism,” The Journal of Christian Reconstruction, Symposium on the Millennium, ed. Gary North, 3:2 (Winter 1976–77), 53–55. [↩]

- Jordan, Esther in the Midst of Covenant History, 5–7. [↩]

- Jordan, Esther in the Midst of Covenant History, 7. [↩]

- Grant R. Jeffrey, The Next World War: What Prophecy Reveals About Extreme Islam and the West (Colorado Springs, CO: WaterBrook Press, 2006), 143, 147–148. [↩]

- In the First Targum to Esther, an Aramaic translation of the Hebrew Bible, the following is found: “The measure of judgment came before the Lord of the whole world and spoke thus: Did not the wicked Haman come down from Susa to Jerusalem in order to hinder the building of the house of thy Sanctuary?” ((Lewis Bayles Paton, A Critical and Exegetical Commentary on the Book of Esther [New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, (1908) 1916], 194. [↩]

- Sverre Bøe, Gog and Magog: Ezekiel 38–39 As Pre-Text for Revelation 19, 17–21 and 20, 7–10 (Wissunt Zum Neun Testament Ser. II, 135) (Tübingen, Germany: Mohr Siebeck, 2001), 384. Anton Scholz (1892), taking an allegorical approach, comments: “The Book of Esther is a prophetic repetition and further development of Ezekiel’s prophecy concerning Gog.” Quoted in Paton, A Critical and Exegetical Commentary on the Book of Esther, 56. The point in all these Gog-Agagite references is to show that there are a number of scholars who see a literary parallel between Ezekiel 38–39 and Esther. [↩]

- Paton, A Critical and Exegetical Commentary on the Book of Esther, 194. [↩]

- Paton, A Critical and Exegetical Commentary on the Book of Esther, 194. “When 93a makes him a Gogite (cf. Ez. 38–39), and L makes him a Macedonian, these are only other ways of expressing the same idea. . .” (194). [↩]

- Jordan, Esther in the Midst of Covenant History, 7. [↩]

- Jordan, Esther in the Midst of Covenant History, 7. This is quite different from identifying the common Hebrew word rosh with modern-day Russia since there is only one common letter between rosh and Russia. See Why the End of the World is Not in Your Future for additional information on the identity of rosh. [↩]

- Mark U. Edwards, Jr., Luther’s Last Battles: Politics and Polemics, 1531–46 (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1983), 97. [↩]

- Peter Toon, “Introduction,” Puritans, the Millennium and the Future of Israel: Puritan Eschatology 1600 to 1660 (London: James Clarke & Co. Ltd., 1970), 19–20. [↩]