This is Not the Way to Answer This Bible Question

Theologian and pastor John Piper was asked by a Christian from Switzerland “why Jesus has not yet returned despite promises made some 2,000 years ago in the Bible.” Here’s how the questioner framed his argument:

As I was studying with our children the need to evaluate prophets by biblical criteria the following thought hit me: The Bible says in Deuteronomy 18 that a prophet whose predictions don’t come true is not sent by God and that he should not be feared. However, in the New Testament we find repeated evidence of people whom we would call inspired who evidently believed — and sometimes claimed — that Jesus would come back soon, even during the writer’s own lifetime. Examples would be 1 Peter 4:7; Matthew 24:34; 26:64; 1 Corinthians 10:11; 1 Thessalonians 4:15-17; and 1 Corinthians 15:51. How can we still consider them authoritative while discarding modern-day messengers whose prophecies don’t materialize? I am a bit uneasy that at some stage our kids will tell us that Paul was wrong about 1 Corinthians 15:51 and so he’s not to be taken seriously. Do you have any suggestions as to how to deal with this tension?”

This inquiry is easy to answer if (1) you take Jesus at His word and (2) you let Scripture interpret itself. This questioner is not the first to raise this objection. Bart Ehrman mentioned it in his book Misquoting Jesus, ((Bart D. Ehrman, Misquoting Jesus: The Story Behind Who Changed the Bible and Why (New York: HarperCollins, 2005).)) and

Christopher Hitchens tried to use it against the reliability of the Bible in his debate with Douglas Wilson in the film Collision. You can read the exchange between Hitchens and Wilson in Collision: The Official Study Guide.

Christopher Hitchens tried to use it against the reliability of the Bible in his debate with Douglas Wilson in the film Collision. You can read the exchange between Hitchens and Wilson in Collision: The Official Study Guide.

The well-known atheist Bertrand Russell argued similarly in his Why I Am Not a Christian:

[Jesus] certainly thought that His second coming would occur in clouds of glory before the death of all the people who were living at that time. There are a great many texts that prove that and there are a lot of places where it is quite clear that He believed that His coming would happen during the lifetime of many then living. That was the belief of His earlier followers, and it was the basis of a good deal of His moral teaching. ((Bertrand Russell, Why I Am Not a Christian (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1957), 16.))

Writing for the Skeptical Inquirer, Gerald A. Larue takes the same position and concludes that the Bible cannot be trusted because Jesus was wrong about the timing of His coming. “Jesus was wrong. Indeed, during the second century CE, some Christians asked, ‘Where is the promise of His coming? For ever since the fathers fell asleep, all things have continued as they were from the beginning of creation.’ (2 Peter 3:4). All we can say is that from that time on, every prophetic pronouncement of the ending of time has been wrong.” ((Gerald A. Larue, “The Bible and the Prophets of Doom,” Skeptical Inquirer (January/February 1999), 29.))

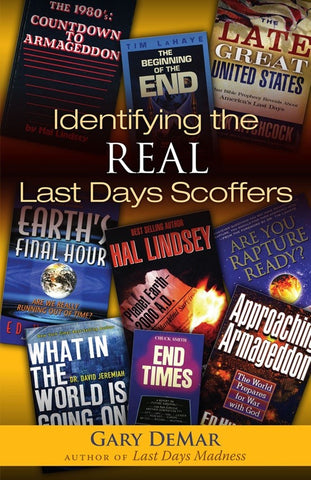

Contrary to Larue, 2 Peter was written a few years before the destruction of Jerusalem, not in the second century. The scoffers are questioning Jesus’ prediction that He would come in judgment against Jerusalem resulting in the destruction of the temple before their generation passed away. As Jesus predicted, it took place a few years after Peter wrote his letter when the Romans destroyed the temple and city in AD 70. For a detailed study of this and other related prophetic topics, see my book Identifying the Real Last Days Scoffers.

Jesus was not predicting a distant physical coming to earth to set up a millennial kingdom. He was predicting a judgment coming on the city of Jerusalem that would result in a great tribulation (Matt. 24:21) and the dismantling of the temple (24:2) before their generation passed away (24:34).

Jesus was not predicting a distant physical coming to earth to set up a millennial kingdom. He was predicting a judgment coming on the city of Jerusalem that would result in a great tribulation (Matt. 24:21) and the dismantling of the temple (24:2) before their generation passed away (24:34).

Jesus’ prediction came to pass just like He said it would. Why would the early church pass around copies of the gospels and letters if there was a glaring problem with a prediction Jesus made in three of the gospels (Matt. 24; Mark 13; Luke 17:22-37; 19:41-44; 21)? It was this fulfillment of Jesus’ prediction that gave credibility to the testimony of Jesus and the reliability of the books of the New Testament.

Unfortunately, Pastor Piper does not do a decent job answering the objection raised by the questioner. Piper’s comments are in bold.

First, sometimes the events that are expected soon are not the very coming of Jesus, but things leading up to the coming of Jesus. Here’s an example: Matthew 24:33, “So also, when you see all these things, you know that he is near, at the very gates.” Next verse, and this is the problem verse for a lot of people: “Truly, I say to you, this generation will not pass away until all these things take place” (Matthew 24:34).

Each time the words “near,” “at hand,” and “shortly” are used in the New Testament they mean what you and I understand them to mean otherwise why did the translators in every modern translation translate them that way? These words can’t be describing an event that’s 2000 years in the future. If these words don’t mean what they mean in normal conversation, then what words could Jesus and the New Testament writers have used if they wanted to make it clear that certain prophetic events were “near” and “at hand”?

Piper writes, “when the New Testament speaks of the Lord being near or at the gates or at hand, it is not teaching a necessary time frame for the Lord’s appearance.” Contrary to what he argues, the word “near” or “at hand” does address a time frame that is in the near future of the present audience. The Greek word ἐγγύς (engus), often translated as “near” or “at hand,” carries the following definition in terms of “time”: “concerning things imminent and soon to come to pass: Matthew 24:32; Matthew 26:18; Mark 13:28; Luke 21:30, 31; John 2:13; John 6:4; John 7:2; John 11:55; Revelation 1:3; Revelation 22:10 of the near advent of persons [Phil. 4:5] … at the door [Mt. 24:33; Mk. 13:29] … near to being cursed [near to disappear] [Heb. 8:13].” ((Thayer, Greek-English Lexicon of the New Testament, “ἐγγύς,” 164-165.)) Also, “‘near, close by (regarding position: spiritually or physically); soon (near in time).’” Any concordance will show that ἐγγύς is almost always used to refer to what is near in terms of time and distance. I don’t recall any exceptions. Kenneth L. Gentry writes:

I urge you: Check any modern English translation. Consult your own favorite version. You will discover that they all speak of temporal nearness… This word commonly speaks of events near in time, such as an approaching Passover (Matt 26:18), the coming of summer (Matt. 24:32), and a soon occurring festival (John 2:13). Again, check any modern version; the results will be the same. (The Book of Revelation Made Easy (Powder Springs, GA: American vision Press, 2010), 19.))

Notice how ἐγγύς is used in Luke’s version of the Olivet Discourse (Luke 21:8, 20, 28, 30, 31). Does ἐγγύς mean something different in each of these verses?

What about, “so, you too, when you see all these things, recognize that He/it is near, right at the doors” (Matt. 24:33)? Notice that “near” means “right at the doors.” What does “right at the doors mean”? It certainly doesn’t mean some doors in a distant country in a distant time. Who would ever say “it’s right at the doors” and mean a set of doors far in the distance or in another era? In Revelation 3:20 we find, “Behold, I stand at the door and knock; if anyone hears My voice and opens the door, I will come in to him and will dine with him, and he with Me.” We see something similar in the epistle of James:

“Therefore, be patient, brethren, until the coming of the Lord. The farmer waits for the precious produce of the soil, being patient about it, until it gets the early and late rains. You too be patient; strengthen your hearts, for the coming of the Lord is near. Do not complain, brethren, against one another, so that you yourselves may not be judged; behold, the Judge is standing right at the door” (vv. 7-9).

A farmer would be discouraged if he planted some seed and it did not germinate before the start of summer. It’s hard to be patient about something that is said to be “near” but hasn’t happened for nearly 2000 years. The patience is related to the promise made by Jesus that His coming in judgment and the old covenant age would pass away before their generation passed away (Matt. 24:34). Once again, we see that “near” is defined as “right at the door.”

Let’s take another look at Matthew 24:33. Note the audience relevance: “when you see all these things, you know that He/it is near, at the doors.” The “you” refers to those in Jesus’ audience, not some unidentified group of people in a distant time.

What about “this generation”? Each time “this generation” is used in the gospels, it always refers to the generation to whom Jesus was speaking (Matt. 11:16; 12:39; 41, 42, 45; 17:17; 23:36; Mark 8:12; 13:30; Luke 7:31; 11:29, 30, 31, 32, 50, 51; 17:25; 21:32). There are no exceptions. It does not refer to a future generation (Jesus would have used “that generation”); it does not mean “race” (Jesus would have used the Greek word genos and not genea); it does not refer to a “kind” or “type” of generation (Jesus does not say, “this type of generation will not pass away”); it does not say “the generation that sees these signs will not pass away” as if to say that it’s a generation different from the one to whom Jesus was speaking. Jesus said, “when you see all these things, you know that he is near, at the very doors.” Their generation was the generation Jesus was referencing.

Pastor Piper continues with an argument that falls apart when Scripture is compared with Scripture:

“Now, notice carefully the phrase, ‘all these things’ that are going to take place within a generation, does not include the actual coming of the Lord, because in the previous verse it says, ‘When you see all these things,’ the very phrase of verse 34 used in verse 33, ‘You know that he is near,’ not already here. The fact that these things will happen within a generation, these preparations for his coming, does not mean that his coming would happen in a generation.”

The coming of the Lord is one of “these things” (Matt. 24:27) since Jesus states, “Truly I say to you, this generation will not pass away until all these things take place” (Matt. 24:34). “All these things” refers to everything before verse 34. That includes His coming in judgment (24:27) so that not one stone of the temple will be left upon another (24:2), His enthronement (24:30; 26:64; cf. Dan. 7:13), and the “end of the age” (Matt. 24:3) all three of which took place before their generation passed way.

There’s some debate over whether the text should read “it is near” (as the AV, KJV, NIV, YLT, and other translations translate ἐγγύς) or “He is near.” The Greek is not definite since the subject “he” or “it” is part of the verb “is” (third person singular). Since “the end of the age” (24:3) is the topic, it’s possible that “it” refers to “the end of the age” that was near. If Jesus was referring to Himself, He would have said, “I am near, at the doors.”

In the Cambridge Greek Testament for Schools and Colleges, we find that “the siege of Jerusalem prefigured by [the fig tree] ‘parable’ took place at the time of harvest. . . ὅτι ἐγγύς ἐστιν [that it is near] The harvest time of God — the end of this æon or period at the fall of Jerusalem.” ((A. Carr, Matthew: Cambridge Greek Testament for Schools and Colleges (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1893), 272.))

Daniel Whedon (1808-1885) offers a similar interpretation in his commentary on Matthew:

These things — The these things specified in the apostle’s question, Matthew 24:3. It is near — There is no supplied antecedent to this it. The meaning, however, is plain. When ye see the train of calamitous events passing successively before your eyes, know that the ruin which is included in the train is near. At the doors — Like the Roman at the portal of the temple. ((Commentary on the Gospels: Matthew and Mark: Intended for Popular Use (Carlton & Porter, 1860).))

While the above interpretation has many adherents, when we compare Matthew 24:33 with its parallel in Luke 21:31, we know what was near: “So you also, when you see these things happening, recognize that the kingdom of God is near.” Jesus was referring to the nearness of the kingdom, a message that was preached up until the time the temple was destroyed (Acts 28:30-31). John the Baptist said, “Repent, for the kingdom of heaven is at hand” (Matt. 3:2). Continuing John’s ministry of repentance, “From that time Jesus began to preach and say, ‘Repent, for the kingdom of heaven is at hand’” (4:17). Jesus told His disciples, “And as you go, preach, saying, ‘The kingdom of heaven is at hand’” (10:7). What would these first hearers of the disciples’ preaching have concluded when they heard them say, “the kingdom of heaven is at hand”? Would they ever have assumed that “at hand” did not mean “at hand”?

N.T. Wright’s comments on the parallel passage in Mark 13 offer a good summary of the issue:

It should be noted most carefully that the signs do not mean that ‘he is near’, as most English translations of Mark 13.29 and its parallels suggest. The Greek is engus estin, which can mean ‘he is near’ or ‘she is near’, or ‘it is near’. In the present context the last of these is both natural and obvious. Luke has paraphrased, just in case (perhaps) anyone should read Mark [or Matthew] without understanding: when you see these things, you will know that the kingdom of God is near. Here we are in touch, I suggest, with the final moments in Jesus’ retelling of the kingdom-story. Luke has rightly brought out the meaning of the entire prediction. When Jerusalem is destroyed, and jesus’ people escape from the ruin just in time, that will be YHWH becoming king, bringing about the liberation of his true covenant people, the true return from exile, the beginning of the new world order. ((N.T. Wright, Jesus and the Victory of God (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 1996), 364.))

Contrary to what Pastor Piper writes, we are not in the last days. Paul writes, “Now these things happened to them [the Israelites in the wilderness] as an example, and they were written for our instruction, upon whom the ends of the ages have come” (1 Cor. 10:11). The “our” refers to those living in Paul’s day.

Speaking of the redemptive work of Jesus, the author of the book of Hebrews writes, “Otherwise, He would have needed to suffer often since the foundation of the world; but now once at the consummation of the ages He has been manifested to put away sin by the sacrifice of Himself” (Heb. 9:26). The “consummation of the ages” was their “now.” The letter to the Hebrews opens with these words:

“God, after He spoke long ago to the fathers in the prophets in many portions and in many ways, in these last days has spoken to us in His Son, whom He appointed heir of all things, through whom also He made the world” (Heb. 1:1-2).

In Peter’s first epistle, we read, “For He was foreknown before the foundation of the world, but has appeared in these last times for the sake of you” (1 Pet. 1:20). The “last times” was their times. That’s why Peter could write, “The end of all things has come near” (1 Pet. 4:7). Not the end of the space-time universe – the physical cosmos ((The disciples ask about the “end of the age” (aion), not the “end of the world” (kosmos) as the KJV has it (24:3).)) – but the remnants of the Old Covenant. The Old Covenant age passed away when the outward symbol of that age – the temple and sacrificial system – was torn down so that “not one stone was left upon another” (Matt. 24:2). Jesus is everything the temple was a placeholder for.

The use of “coming” in the Bible (Old and New Testaments) is not always a reference to what is typically identified as Jesus’ Second Coming (e.g., Rev. 2:4, 16, 25; 3:3). That’s especially true in the Olivet Discourse.

How would I have answered the questioner?: “Jesus and the New Testament writers are describing events related to the end of the Old Covenant Age and not the end of the world or Jesus’ so-called Second Coming. This means words like ‘near,’ ‘shortly,’ and ‘this generation’ make perfect prophetic sense.”

There’s a great more that I could write in response to Pastor Piper’s comments, but I’ve covered these topics elsewhere. My new book Wars and Rumors of Wars should be available either late July or early August. It’s a detailed exposition of Matthew 24:1-34. For expositions of other passages, see my books Last Days Madness, Prophecy Wars, 10 Popular Prophecy Myths Exposed and Answered, and The Gog and Magog Alliance. For an introduction on how to interpret Bible prophecy, see A Beginner’s Guide to Interpreting Bible Prophecy.