Atheists and Liberals Go Insane Over Trump’s Executive Order on Religion

President Donald Trump signed an executive order on May 4, the National Day of Prayer, “that allows churches and other religious organizations to become more active politically, according to officials.”

While conservatives were hoping for more, atheists and liberal Democrats were hoping for less, except in black churches where Democrats have been politicking for decades with nary a peep from the ACLU and Americans United for Separation of Church and State. I’m not sure if atheist groups have officially protested and brought a suit against any minority churches.

As I mentioned in a previous article, the long-term goal of atheists is to remove every vestige of Religion from American life, starting with the small towns and moving to the large leftist cities. Once the only real competitor to Islam is eradicated, the atheists themselves will be eradicated.

Like clockwork, The Freedom From Religion Foundation has brought suit against the Trump administration:

“The Freedom From Religion Foundation filed suit Thursday in federal court against Trump and the Internal Revenue Service, claiming the order is unconstitutional because it makes government favor religion over nonreligion. Although the executive order applies to all nonprofits, FFRF believes it will be selectively enforced so as to only benefit churches and religious organizations. (The Daily Beast)

After Trump signed his Executive Order, an ABC affiliate offered this poll question: “Should religion be allowed in politics?”

The question is poorly constructed (on purpose?) since religion has always been part of American politics. What constitutes religion? Who gets to decide? The Declaration of Independence mentions God four times and the Constitution references it in its closing statement. Unconstitutional?:

1. The Laws of Nature and Nature’s God…

2. Endowed by their Creator…

3. The Supreme Judge of the world…

4. The protection of divine Providence…

This is no deistic God. He is a God who endows, judges, and protects.

The First Amendment states: “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion or prohibiting the free exercise thereof. . .” This means anyone, pastors of churches included, can, speak, write, assemble on the subject, and petition the government when religion or any other issue arises. In fact, the First Amendment also applies to atheists. They are free not to have a religion, and Congress cannot pass a law infringing on their rights to speak (freedom of speech), publish (freedom of the press), assemble, and petition the government for a redress of grievances, which they are doing.Notice, however, that the Constitution specifically protects religion making the FFRF off base in its criticism.

Notice, however, that the Constitution specifically protects religion — “Congress shall make not law . . . prohibiting the free exercise” of religion — making the FFRF off base in its criticism. Notice the Amendment does not say, “except when it comes to politics.”

The 1954 Johnson Amendment is a clear violation of the First Amendment by prohibiting pastors of churches from having the freedoms that other citizens have. It’s not about allowing religion in politics; it’s about being free to address the issues of politics from a religious point of view or any other point of view.

Now to the question, “Should religion be allowed in politics?” What law says it can’t be? Neither the First Amendment or actions of the constitutional framers give evidence against the question. There is ample evidence that they welcomed religion related to its acknowledgment that government is not god, rights are the province of God, and the source of morality is found in God’s immutable character. For example, the first Congress that convened after the adoption of the Constitution requested of the President that the people of the United States observe a day of thanksgiving and prayer:

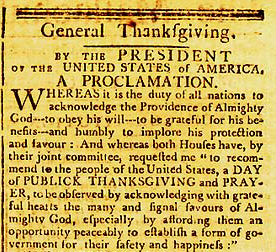

“That a joint committee of both Houses be directed to wait upon the President of the United States to request that he would recommend to the people of the United States a day of public thanksgiving and prayer, to be observed by acknowledging, with grateful hearts, the many signal favors of Almighty God, especially by affording them an opportunity peaceably to establish a Constitution of government for their safety and happiness.”

This resolution was opposed by some as an infringement on the authority of the states: “It is a business with which Congress has nothing to do; it is a religious matter, and as such is proscribed to us.” They did not oppose religion. Their point was that religious issues are the domain of the states (First, Ninth, and Tenth Amendments) as the state constitutions of the time make very clear.

Nevertheless, the resolution was adopted. George Washington then issued a proclamation on October 3, “in the year of our Lord 1789,” as a national day of thanksgiving, calling everyone to “unite in most humbly offering our prayers and supplications to the great Lord and Ruler of Nations, and beseech him to pardon our national and other transgressions.” Why? Because “it is the duty of all nations to acknowledge the providence of Almighty God, to obey His will, to be grateful for His benefits, and humbly to implore His protection and favor.”

Washington called for days of prayer and thanksgiving on January 1 and February 19, 1795.

Bishop Samuel Provost

One of the first orders of business of the first Congress was to appoint chaplains. Bishop Samuel Provost and Reverend William Linn became paid chaplains of the Senate and House respectively. Since then, both the Senate and the House have continued regularly to open their sessions with prayer.