Why Papa Ruins Everything: Unicorns, Fairies, and Elves

On Friday, I picked up three of my grandchildren from school. Two of the youngest (kindergarten and first grade) were talking about elves and fairies. This is not surprising since these mythical creatures are everywhere in children’s literature and popular films. I may have ruined their weekend when I reminded them that elves and fairies aren’t real. I think they already knew this, but I wanted to make sure.

It’s never too early to help your children and grandchildren learn to think critically. Use whatever is available to help them think through a claim or argument. Be open to their questions and don’t crush their inquisitive and imaginative nature.

I told them the story of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, the creator of the Sherlock Holmes character, who was an ardent believer in psychic phenomena and all manner of spiritualist nonsense. Doyle also believed that Harry Houdini (1874-1926), the greatest magician of his era, performed his various disappearance “tricks” by supernatural means. (Houdini never could convince him otherwise.) How is it, then, that the Holmes’ character was so analytical and his creator, Doyle, was so gullible, always looking for a preternatural explanation for everything? It’s hard to understand.

One of the most bizarre incidents in Doyle’s life was the “Cottingley Fairies” hoax. “The case involved what Conan Doyle believed was photographic evidence of the existence of fairies, documented by two young Yorkshire girls, Elsie Wright and her cousin Frances Griffiths.”

The most famous of the photographs is below. Can you spot the one thing in the photo that demonstrates that the cut-out-looking fairies are a hoax?

In the background, there is a waterfall. In 1917, when the above photo was taken, high-speed film did not exist. The shutter of the camera had to stay open for around 10 seconds so enough light would impact the exposed film. This meant that the photographed subjects could not move otherwise they would appear blurry.

While the waterfall is blurry, as you would expect, the wings on the flying and flittering fairies are perfectly still. Watch the short video by James Randi who explains how the hoax should have been easily detected by the author of the great fictional observational detective Sherlock Holmes. Holmes would have spotted the visual contradiction immediately:

In addition to elves and fairies, young girls are into unicorns. They’re pasted and plastered on everything from shirts and shoes to bookbags and lunchboxes. They, too, are fictional, at least the equine version of the mythical creatures.

A skeptic wrote to me some time ago and pointed out that the Bible mentioned mythical creatures called “unicorns” (Num. 23:22; 24:8; Deut. 33:17; Job 39:9-10; Ps. 22:21; 29:6; 92:10; Isa. 34:7). Since these creatures did not exist, he argued the Bible must not be accurate, thus, invalidating the authority and inspiration of the Bible.

A unicorn is an animal with one (uni) horn. When the Hebrew Bible was translated into Greek, the Hebrew word ראם (re’em) was not easy to translate. The Greek translators used the word monokeros that means “one-horned.” The thing of it is, there’s nothing in the Hebrew word that indicates that the animal is a one-horned animal. John Gill wrote, “whatever is meant by the term … must be a strong creature” (Deut. 33:17).

When Jerome translated the Bible into Latin, he translated the Greek monokeros as unicornis, which also means one-horned without any of the connotations attached to modern-day mythical creatures. When the translators of what would become the King James Version saw the word unicornis, they transliterated it as “unicorn.” The translators of the KJV or Authorized Version (AV) were brilliant and careful translators. Consider the following:

[On Isaiah 34:7] in the 1611 edition, the AV translators wrote two slashes || in front of the word UNICORN. Those slashes are known as a siglum, and the 1611 edition makes use of sigla throughout. In the adjacent margin — directly across from this siglum — the AV translators repeat that same siglum, i.e., they write the same two slashes ||, and then immediately after that they write – “or Rhinocerots” which was the term for the RHINOCEROS in 1611, derived from the Latin UNICORNIS and the Greek MONOKEROS, both meaning ONE-HORNED, and both referring to the RHINOCEROS-type creature.

In other words, the AV translators themselves stated that they were equating UNICORN with RHINOCEROS or a type of animal resembling a rhinoceros.

Robert Young in his Concise Critical Comments on the Holy Bible does not translate the Hebrew word re’em. He simply transliterates the word and added the following note to Numbers 23:22: “The exact animal meant is not certain. The [Greek] Septuagint and [Latin] Vulgate have ‘unicorn’; Gesenius, ‘buffalo.’”

None of the translators – Hebrew, Greek, or English – had “a mythical unicorn dancing among rainbows” in mind when they translated the Hebrew word re’em as a one-horned animal.

Noah Webster’s 1828 Dictionary of the English Language offers the following definition and explanation of the meaning of the English-coined word “unicorn”:

U’NICORN, n. [L. unicornis; unus, one, and cornu, horn.]

- an animal with one horn; the monoceros. This name is often applied to the rhinoceros.

- The sea unicornis a fish of the whale kind, called narwal, remarkable for a horn growing out at his nose.

Webster does not mention a horse, a horse-like animal, or imply that it’s a mythical creature.

Today, the rhinoceros that we’re familiar with has two horns. But according to two Webster there were two species, a single horn or “unicorn” and a two-horned or “bicornis” animal. The one-horned rhinoceros’s scientific name is Rhinoceros unicornis. The Black Rhinoceros is designated as Diceros bicornis. If the Bible is unscientific, then so is modern-day science since “there are five species of the rhinoceros, three of which have two horns, and two of which have one horn.” And because a one-horned animal in Latin is unicornis, the animals are called “unicorns.” Skeptics are conflating two different ideas by projecting modern-day unicorns on a book that was translated more than 400 years ago using Hebrew, Greek, and Latin.

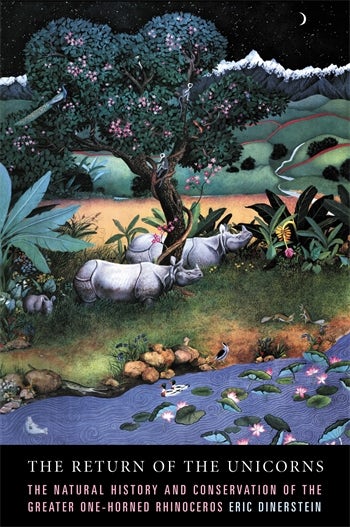

In 2003, the book The Return of the Unicorns: The Natural History and Conservation of the Greater One-Horned Rhinoceros, written by an evolutionary scientist named Eric Deinerstein, was published and is available on Amazon.

Note that the cover has a picture of the Rhinoceros, a unicorn:

The following image is found on page 11 of his book under the chapter title “Vanishing Mammals”:

Scientists today often use the word “unicorn” when referring to either the Asian One-Horned Rhinoceros or the Javan Rhinoceros. If you do any research online, you’ll find scientists often calling them “unicorns.” The Asian One-Horned Rhinoceros is also known as the Indian Rhinoceros and also as the Greater One-Horned Rhinoceros.

There is an extinct species of a giant one-horned rhinoceros called Elasmotherium sibiricum. Here’s a picture of the first published restoration (1878) of E. sibiricum. The internet is filled with extinct one-horned animals. Their scientific names would identify them as unicorns.