Terrorism and Violence for Social Change are Tactics of the Left

Once again liberals want to blame a murder spree on conservatives. Somehow Dylann Roof represents conservatives because he used a gun to kill 9 innocent black people in church and likes the Confederate Battle flag. Liberals did a similar thing with the Oklahoma City bombing.

And what’s a liberal’s solution? Take legally-owned guns from 99.9 percent of the population and take down the Confederate Battle Flag in South Carolina.

Timothy McVeigh did not use a gun to kill 167 people, and a flag did not contribute to the evil that lurks in the heart of Dylann Roof. If a flag was the problem, then one has to ask why Democrats have used the Confederate Battle Flag in support of Democrat candidates for decades with no apparent violence.

Dylann Roof’s attempts to cause social disruption (a race war) are the tactics of the left. Charles Manson also wanted to start a race war. In his case, he planned to murder white people and then blame it on blacks. He called it “Helter Skelter.”

“That Manson foresaw a war between the blacks and the whites was not fantastic. Many people believe that such a war may someday occur. What was fantastic was that he was convinced he could personally start that war himself—that by making it look as if blacks had murdered the seven Caucasian victims he could turn the white community against the black community.” ((Vincent Bugliosi, with Curt Gentry, Helter Skelter: The True Story of the Manson Murders (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1974), 222.))

Manson was no conservative.

In the July 11, 1968, issue of The Village Voice, Marvin Garson, the pamphleteer of the Free Speech Movement, recounted with pride the bombings which had been the calling card of campus radicals from Berkeley and its environs:

“The series of successful and highly popular bombings which have occurred here recently: the steady bombing of the electric power system from mid-March when the lines leading to the Lawrence Radiation Lab were knocked down, to June 4, when on the morning of the California primary 300,000 homes in Oakland were cut off; the dynamiting of a bulldozer engaged in urban renewal destruction of Berkeley’s funkiest block; three separate bombings of the Berkeley draft board; and finally, last Tuesday night, the dynamiting of the checkpoint kiosk at the western entrance to the University campus, a symbol of the Board of Regent’s property rights in the community of scholars.” ((Quoted in Lewis S. Feuer, The Conflict of Generations: The Character and Significance of Student Movements (New York: Basic Books, 1969), 479.))

Left-wing Weathermen were even more radical. They too were into bombs. “On March 6, 1970, a tremendous explosion demolished a fashionable Greenwich Village townhouse, and from the flaming wreckage fled two SDS ‘Weatherwomen,’ members of the SDS terrorist faction. In the rubble police found remains of a ‘bomb factory’ and three bodies, including one of the organizers of the 1968 Columbia University rioting and another of a ‘regional traveler’ who had helped spark the Kent State buildup.

“Four days later in Maryland two close associates of Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) firebrand H. ‘Rap’ Brown blew themselves to smithereens while apparently transporting a bomb to the courthouse where their cohort was to stand trial on an inciting riot charge. . . . Also, in 1970 a Black Panther carrying a bomb along a Minneapolis street blasted himself to bits. Despite the carnage to themselves, Panther and Weatherman terrorists succeeded in setting off bombs in the New York City police headquarters, the U.S. Capitol, and scores of other public and corporate buildings across the nation.” ((Eugene H. Methvin, The Rise of Radicalism: The Social Psychology of Messianic Extremism (New Rochelle, NY: Arlington House, 1973), 513.))

In addition, they had succeeded in setting off bombs in the Pentagon and several major courthouses. “These were the bombings they took credit for publicly. The full extent of their terrorist activities remains unknown.” ((Stanley Rothman and S. Robert Lichter, Roots of Radicalism: Jews, Christians, and the New Left (New York: Oxford University Press, 1982), 42.))

By the late 1960s and early 1970s, there was a resurgence of left-wing radicalism that led to violence with hope to build a better world. On May 7, 1967, just weeks before the riot in Newark, New Jersey, Greg Calvert of SDS described its members as “post-communist revolutionaries” who “are working to build a guerrilla force in an urban environment. We are actively organizing sedition.” ((New York Times (May 7, 1967). Quoted in Eugene H. Methvin, The Rise of Radicalism: The Social Psychology of Messianic Extremism (New Rochelle, NY: Arlington House, 1973), 497 and The Riot Makers: The Technology of Social Demolition (New Rochelle, New York: Arlington House, 1970), 27.))

The SDS was a growing radical movement made up of college students. The rhetoric of the SDS was at its core anti-government. “SDS organizers denounced ‘oppressors,’ ‘exploiters,’ and ‘the Al Capones who run this country.’ The university was depicted as a ‘colony’ of ‘the military-industrial complex’ and a ‘midwife to murder.’ ‘Imperialism’ was offered as a convenient scapegoat for every frustration and failure.” ((Methvin, Rise of Radicalism, 504.))

A keynote speech at a 1962 SDS convention praised the freedom riders, not for furthering civil rights but rather for their “radicalizing” potential, their “clear-cut demonstration for the sterility of legalism.” The speaker continued:

“It is not by . . . ‘learning the rules of the legislative game’ that we will succeed in creating the kind of militant alliances that our struggle requires. We shall succeed through force — through the exertion of such pressure as will force our reluctant allies to accommodate to us, in their own interest.” ((Thomas Kahn, “The Political Significance of the Freedom Riders,” in Mitchell Cohen and Dennis Hale, eds., The New Student Left (Boston, Massachusetts: Beacon Press, 1966), 59, 63. Quoted in Rothman and Lichter, Roots of Radicalism, 13.))

Some campus radicals in the 1960s pursued the conviction “that violence may be necessary” to bring about any meaningful cultural change in America. A student from the University of California at Berkeley stated that she understood why certain groups riot. “I feel the same frustrations in myself, the same urge to violence.” ((Feuer, The Conflict of Generations, 478.)) Such sympathies are prevalent among today’s liberals when their opinions are surveyed regarding Palestinian suicide terrorists. Self-sacrifice for an ultimate cause, although not in such extreme measures, was born and bred in the USA. The campus at Berkeley led the way.

In 1967 the national secretary of SDS declared himself to be a disciple of Che Guevera: “Che’s message is applicable to urban America as far as the psychology of guerrilla action goes. . . . Che sure lives in our hearts.” “Black power,” he added, “is absolutely necessary.” White student activists noted that “black nationalists are stacking Molotov cocktails and studying how they can hold a few city blocks in an uprising, how to keep off the fire brigade and the police so that the National Guard must be called out. . . .” ((Feuer, The Conflict of Generations, 478.)) Domestic terrorism is writ large in our history, but few people remember it.

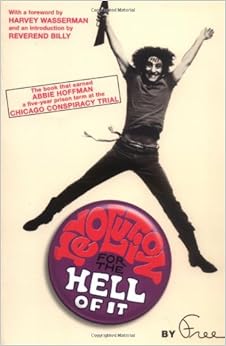

On the cover of Revolution for the Hell of It, Abbie Hoffman, the Yippie spokesman of the 1960s, is pictured with a rifle in his hand leaping for joy. Hoffman envisioned and encouraged today’s sexual revolution and the general disembowelment of morality. Hoffman went further by supplying information that he hoped would lead to the violent overthrow of “the system”:

On the cover of Revolution for the Hell of It, Abbie Hoffman, the Yippie spokesman of the 1960s, is pictured with a rifle in his hand leaping for joy. Hoffman envisioned and encouraged today’s sexual revolution and the general disembowelment of morality. Hoffman went further by supplying information that he hoped would lead to the violent overthrow of “the system”:

“To enter the twenty-first century, to have revolution in our lifetime, male supremacy must be smashed, . . . A militant Gay Liberation Front has taught us that our stereotypes of masculinity were molded by the same enemies of life that drove us out of Lincoln Park. . . . Cultural Revolution means a disavowal of the values; all values held by our parents who inhabit and sustain the decaying institutions of a dying Pig Empire.” ((Abbie Hoffman, Revolution for the Hell of It (New York: Pocket Books, [1968] 1970), 3.))

Hoffman’s rhetoric about revolution was just a warm-up. In Steal This Book he gave instructions on how to build stink bombs, smoke bombs, sterno bombs, aerosol bombs, pipe bombs, and Molotov Cocktails. Hoffman’s updated version of the Molotov Cocktail consisted of a glass bottle filled with a mixture of gasoline and Styrofoam, turning the slushy blend into a poor man’s version of napalm. The flaming gasoline-soaked Styrofoam was designed to stick to policemen when it exploded. ((Abbie Hoffman, Steal This Book (New York: Pirate Editions, 1971), 170–79.)) Helpful drawings on how to make the incendiary devices are included.

In Woodstock Nation, Hoffman updated his revolutionary tactics. This time, Random House is the publisher. Next to Random House’s name on the title page, there is an illustration of a man blowing up a house with dynamite.

This same illustration appears in Hoffman’s Steal This Book. The theme of both books is how to blow up the system, literally. Hoffman informs us that “the best material available on military tactics in revolutionary warfare” is available through “the U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, D.C.”

“Another publication that’s probably the most valuable work of its kind available is called Physical Security and has more relevant information than Che Guevara’s Guerilla Warfare. The chapter on Sabotage is extremely precise and accurate with detailed instructions on the making of all sorts of homemade bombs and triggering mechanisms. That information, combined with Army Installations in the Continental United States and a lot of guts, can really get something going?”

Of course, Hoffman never advocates blowing up anything or anyone. “I ain’t saying you should use any of this information, in fact for the records of the FBI, I say right now ‘Don’t blow up your local draft board or other such holy places.’ You wouldn’t want to get the Government Printing Office indicted for conspiracy, would you now?” ((Hoffman, Woodstock Nation, 114.)) He’s just making the information available. You know, freedom of expression and all of that. Then he reproduces pages from the Department of the Army Field Manual dealing with “Disguised Incendiary Devices,” “Mechanical Delay Devices,” and pipe bombs. ((Hoffman, Woodstock Nation, 115–116.))

Then there are these from Hoffman:

- “Off the Pigs!”

- “Personally, I always held my flower in a clenched fist.”

- “Yippies believe in the violation of every law.”

Liberals have short and selective memories when it comes to their own rhetoric and tactics.

“The use of violence was justified, many in the New Left comforted themselves, because theirs was a violence to end all violence, a liberating and righteous violence that would rid the world of a system that deformed and destroyed people. Such glorious ends justified, even ennobled, violent means.” ((Richard J. Ellis, The Dark Side of the Left: Illiberal Egalitarianism in America (Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas, 1997), 137.))

Organizations like Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) and the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) used violent rhetoric almost from their inception in the early 1960s.

John Lewis, the very liberal Democrat representative from Georgia, boasted when he addressed the March on Washington in August 1963, “We will march through the South, . . . the way Sherman did. We shall pursue our own ‘scorched earth’ policy and burn Jim Crow to the ground — nonviolently. We shall crack the South into a thousand pieces and put them back together in the image of democracy.” ((John Lewis, “A Serious Revolution,” The New Left: A Documentary History, ed. Massimo Teodori (Indianapolis, IN: Bobbs-Merrill, 1969), 102))