Sexually Diverse Comic Book Characters as Moral Cultural Wedges

The Season 4 of the TV series Supergirl will debut a trans character who will play Dreamer. “A trans superhero is finally coming to television—and she’s actually being played by a trans actress.” Here’s how one pro-trans site described the upcoming story arc:

Our first trans superhero is coming to TV and a trans activist and actor is bringing her to life. For the first time, trans and cis kids will grow up seeing a trans superhero on TV. For the first time, trans folks of all ages will see themselves reflected in a genius, precognitive, badass fighter who is protective, capable, and powerful. (SyFy Wire)

Such sexual anomalies are part and parcel to today’s comic book universe. It was not always this way. When an average guy turned into flaming and flying Johnny Storm and Peter Parker transitioned into a spider-like human, we shouldn’t be surprised that a man transformed himself into a woman. The difference is that the two Marvel Universe characters’ transitions were the result of gamma rays and a bite from a radioactive spider. There was no lopping off of body parts and hormone treatments.

In addition to a man-who-became-a-woman having a part in Supergirl, the DC Universe is making its Batwoman character a lesbian. Ruby Rose, who will be donning the cape and cowl, posted the following on Instagram post: “This is something I would have died to have seen on TV when I was a young member of the LGBT community who never felt represented on tv and felt alone and different.” As you’ll read below DC outed Batwoman in 2006 in its print edition of the series. Not everyone is happy with the chose of Rose. She’s not quite authentic:

Recurring sentiments appear to be that Batwoman should be played by a Jewish lesbian, and that the role would have been a great opportunity to elevate new talent. Sample tweets include, “Ruby is great… But she is not the only queer actress out there” and “JEWISH LESBIAN CHARACTER SHOULD BE PLAYED BY A JEWISH LESBIAN.” (Daily Beast)

Advocates of the LGBT community run Hollywood. They are never satisfied with their accomplishments. They say “jump,” and Hollywood actors, directors, and producers say, “how high and how long do we have to stay up in the air”?

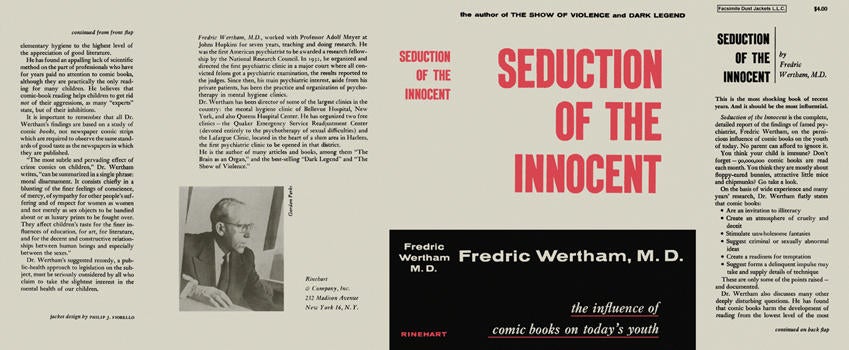

Enter Frederic Wertham and The Seduction of the Innocent

In the late 1940s and early 1950s, the so-called Golden Age of comics, the content of some comic books was raw. ((Mikal Vollmer, Snuff Comics: Golden Age of Torture and Murder—Kids’ Comic Books of the 40’s and 50’s (Solana Beach, CA: Item Comics, 1996).)) These comics came to the attention of New York psychiatrist and part-time comic critic Frederic Wertham (1895–1981) who described them as “blueprints for delinquency.” Writing in The Reader’s Digest in the August 1948 issue, Wertham asked: “Do you think that books which stress murder and mayhem and blood-and-thunder are good for youngsters?” ((Frederic Wertham, “The Comics . . . Very Funny,” The Reader’s Digest (August 1948), 15. The article originally appeared in an unabridged form in the May 26, 1948 issue of The Saturday Review of Literature.)) Similar articles appeared in the Ladies Home Journal, Scouting Magazine, ((Frederic Wertham, “Let’s Look at the Comics,” Scouting (September 1954), 2–3, 19–20.)) and other issues of The Reader’s Digest. Wertham believed that reading comics led to violent criminal behavior in young people. His book Seduction of the Innocent (1954) and his testimony before Congress nearly put an end to the comic book industry until publishers took matters into their own hands and implemented the “Comics Code Authority.”

Marvel Comics, publishers of such popular titles as X-Men, Spider-man, The Fantastic Four, and The Incredible Hulk, officially dropped the code in 2001. Independent publishers like Image and the now-defunct Valiant never adopted the code. But even before the code’s official demise, some comic lines pushed the envelope of good taste and morality by becoming sex-obsessed, anti-Christian, blasphemous, and occultic, points made by John Fulce in Seduction of the Innocent Revisited. But even before the code’s end, Marvel and DC had consistency ignored it. Thor (#330) has the “God of Thunder” fighting the “Crusader,” a not-so-subtle slam at Christian conservatives at the height of the Moral Majority in the 1980s.

Marvel announced in December 2002 that it was reviving the 1950’s character “The Rawhide Kid” as an openly homosexual character. ((Marvel Comics to unveil gay gunslinger” (December 22, 2002): http://archives.cnn.com/2002/SHOWBIZ/12/09/rawhide.kid.gay/)) Brokeback Mountain was a Johnny-come-lately homosexual cowboy story. Marvel was there first. This was the first openly homosexual title character in a comic book published as part of its Marvel Max imprint “alternative Marvel universe” series.

The comic book genre was seen, like all fiction, as “morality tales.” People believed in “truth and justice” as if they were objective realities worth defending. We now live in a morally ambiguous universe. Truth and justice are slippery concepts in a post-modernist way. They’re still there, but they mean different things to so many different people, and it seems that most of us are content to leave it that way.

How Times and Comic Books Have Changed

In the March 1992 issue of Marvel’s Alpha Flight comic book series, Northstar, a former (fictional) Canadian Olympic athlete, decides to come out of the closet after seeing the ravaging effect that AIDS has had on an abandoned baby. He decides to adopt the infant AIDS victim. The editors at The New York Times celebrated this favorable treatment of homosexuality: “[T]he new storylines suggest that gay Americans are gradually being accepted in mainstream popular culture…. Mainstream culture will one day make its peace with gay Americans. When that time comes, Northstar’s revelation will be seen for what it is: a welcome indicator of social change.” ((“The Comics Break New Ground, Again,” The New York Times (January 24, 1992), A12.))

The New York Times, in order to justify its support of homosexuality, compares discrimination of homosexuals with the discrimination of blacks, women, and the handicapped. “Marvel, beginning in the early 1960’s, was the pioneer in comic book diversity. Marvel published ‘Daredevil,’ a dynamic crime fighter who was also blind. Then came ‘The X‑Men,’ a band of heroes led by a scientist whose mental powers more than compensated for his confinement to a wheelchair. And with ‘Powerman,’ ‘The Black Panther,’ and ‘Sgt. Fury,’ Marvel offered black heroes when blacks in the movies were playing pimps and prostitutes.” ((“The Comics Break New Ground, Again,” A12.))

We should not forget Wonder Woman who brought equality to women in the realm of power and multitasking more than 70 years ago and whose creator was a sexual deviant. Now there are many women superheroes. Northstar’s hero team was led by a woman. The second‑largest comic company, Detective Comics (DC), publisher of Batman and Superman, introduced a homosexual character—the Pied Piper—and AIDS‑related themes in their Flash series (August 1991). “Future issues [of Flash] will have the Pied Piper bring a male date to a wedding and discuss the importance of protecting yourself from exposure to AIDS.” ((“Comic Book Hero Says He’s Gay,” The Gwinnett Daily News (January 17, 1992), 4A.)) What is it about homosexuality that one needs to protect oneself from it?

The goal of parading homosexual “heroes” is to get young people—who will one day be decision makers—accustomed to seeing homosexual characters in positions of leadership and authority. Gary Stewart, the president of Marvel Entertainment Group when Northstar was “outed,” had this to say about the introduction of their homosexual “superhero”: “And at the time that … the team was created, Northstar … was considered to be gay by the creator. [In earlier issues] there were hints that he was. There was no direct admission at that time. We believe that the only message here, per se, is the fact that we do preach tolerance. Just as you have in everyday society, you have gay individuals and straight individuals. We happen to have one character in the Marvel universe, which exceeds two thousand characters, that happens to be gay.” ((Interview from “Point of View,” #2274 (January 17, 1992), P.O. Box 30, Dallas, Texas 75221.))

The New York Times, is a bit more honest than the people at Marvel, took an advocacy position. The editors wrote that it was “welcome news.” Since the comic book audience is made up mostly of teenagers, that group “will benefit most from discussions about sexuality and disease prevention.” ((“The Comics Break New Ground, Again,” The New York Times (January 24, 1992), A12.)) According to the Times, Northstar’s homosexuality should be treated like race, physical handicaps, and gender differences. There is a problem with the analogy: homosexuality is a behavioral choice. No one chooses blindness, racial makeup, physical handicaps, or gender. And given a choice, people with physical handicaps, genetic or not, would like their disabilities reversed.

Consider Ben Grimm’s character “Thing” of The Fantastic Four, introduced by Marvel in November 1961. (The ten-cent comic sells for more than $75,000, if you can find one of the seven copies in VF/NM condition.) The other three members of the superhero quartet can turn their newly acquired powers on and off at will. Most of the time they are normal‑looking human beings. This is not the case for Ben Grimm. He is always the rock‑like “Thing.” Reed Richards, “Mr. Fantastic,” is forever working on ways to make Ben normal, or at least to give him the ability to change into the “Thing” at will. Abnormalities should be corrected, and homosexuality is a deviation from the heterosexual norm.

X-Men: Last Stand (2006) revolves around a “mutant cure.” Some mutants are interested in the cure since they’re powers are either physically objectional (Beast) or debilitating (Rogue). “The Mutant Cure is a pharmaceutical designed by Worthington Labs to suppress the X-Gene, causing mutants to lose their powers and/or physically resemble ordinary humans.”

The introduction of homosexual characters is increasing. DC’s “Batwoman,” described as “a ‘lipstick lesbian’ ((A non-stereotypical feminine lesbian rather than a “butch” appearance.)) who moonlights as a crime fighter,” was introduced in 2006. “The new-look Batwoman is just one of a wave of ethnically and sexually diverse characters entering the DC Comics universe.” ((“Batwoman hero returns as lesbian” (May 30, 2006).)) Retro-homosexual history has pronounced the Caped Crusader (Batman) and the Boy Wonder (Robin) to be involved in a “special relationship.”

The homosexual community’s strategy is evident: To soften public opinion to adopt the homosexual lifestyle as morally acceptable using popular culture as the sled. The latest attempt to normalize homosexuality is being made by Stan Lee, the creator of Spider-man, X-Men, and The Fantastic Four:

Lee has reportedly created a character called Thom Creed, a high-school basketball player who is forced to hide his sexuality as well as his superpowers.

It is not known what kind of powers Creed will display. Lee, the former head of Marvel Comics … will unveil Creed in an hour-long television special made in the US. If he proves popular with audiences, the programme will be shown in Britain. Lee developed the idea of a gay character from the award-winning novel Hero by Perry Moore, the [Scottish] Sun reports. A television industry source told the paper: “It was only a matter of time before we had our first gay superhero. And if there is one man who can make him a success it is Stan Lee. There’s a real buzz among comic book fans.”

It remains to be seen whether comic readers will embrace homosexual characters, tolerate them, or give up on comics altogether. The true test will be how the movies present this issue. While there is a homosexual subtext to the X-Men series since two of them were directed by bisexual director Bryan Singer, most people would not pick it up unless it was pointed out to them. The original X-Men comic series was always about alienation, but it was not designed to be a wolf-in-sheep’s-clothing vehicle for promoting homosexuality. Like so much of what’s happening today, it was hijacked.