Leftists Admit They Want to Abolish the Constitution

An op-ed piece in the New York Times by Meagan Day and Bhaskar Sunkara states, “The Byzantine Constitution that [James Madison] helped create serves as the foundation for a system of government that rules over people, rather than an evolving tool for popular self-government.” They go on to write, “As long as we think of our Constitution as a sacred document, instead of an outdated relic, we’ll have to deal with its anti-democratic consequences.”

By getting rid of the Constitution, we would be left with people like Day and Sunkara “ruling over the people” with nothing to stop them but the unbridled will of the majority that they control through the education system, media, and courts. In the Kentucky Resolutions of 1798, Jefferson wrote, “in questions of power then, let no more be heard of confidence in man, but bind him down from mischief by the chains of the constitution.”

While the following is attributed to Jefferson, there is no source for it. Even so, it’s spot on:

The two enemies of the people are criminals and government, so let us tie the second down with the chains of the Constitution so the second will not become the legalized version of the first.

The Constitution makes provision for change. It’s not a sacred document like the Bible, otherwise, there never could be any changes. The fact that we have 17 more Amendments than when the Construction with its Bill of Rights was ratified in 1789 is a testimony to the fact that, while our Founders rejected pure democracy (a form of mob rule), they provided for a democratic process.

On one point I agree with the authors. The Constitution will not save us. Ultimately, only God can save us. That does not mean, however, that He does not hold us to be responsible in the here and now.

Members of the House are elected by majority vote. What Day and Sunkara detest is the Electoral College. They want the mostly liberal population centers to control the nation. We are a nation of states with their own Constitutions and laws. If a person living in California does not like how the elected officials there are running the state, they have the freedom to move to another state. The Electoral College protects less populated states while yielding more power to larger states in the House of Representatives. It’s a balanced system with built-in protections.

Buried at the bottom of the Times article is this: “Meagan Day [is] a writer for the socialist magazine Jacobin…” She would have loved the French Revolution.

A little history will help to put things in perspective for us by looking at the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution as compared to the French Declaration of the Rights of Man along with our nation’s War for Independence and Franc’s bloody Revolution.

Our Declaration of Independence states in unequivocal terms the following:

We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness. — That to secure these rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed.

The above declaration specifies that there are more than just these three rights. There are “certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.” The use of “among these” is important. Note that these rights are not gifts from the State. Neither are these rights created by governments. The logic of the Declaration is clear: No God—no rights.

There was no attempt by the founders to disestablish a biblical moral order by endorsing a moral revolution that is going on today. The colonial (state) governments with their laws, many of which were founded on the Bible, and institutions, including churches and their courts, remained intact. Contrary to some historians, the United States Constitutions did not disestablish Christianity. Yes, there is “no religious test” at the national level, but there remained tests at the state levels. This practice was retained as the First Amendment makes clear:

Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion or prohibiting the free exercise thereof…

The Constitution recognizes Sunday as the Christian Sabbath by setting it aside as a non-work day for conducting official government business (art. 1, sec. 7) and kept the Christian Calendar intact: “DONE in the Year of our Lord….” The “Lord” is the Lord Jesus Christ as the date 1787 attests to. More about this later.

None of the State constitutions, with their many references to religion in general and Christianity in particular, were nullified by the adoption of the Federal Constitution. The Constitution, like the Declaration, assumes an existing moral order that was generally held to be based on “revealed law or divine law” and “the law of nature,” which William Blackstone taught in his multi-volume work Commentaries on the Laws of England was “coeval [existing at the same time] with mankind and dictated by God Himself” (1:41-142).

None of the State constitutions, with their many references to religion in general and Christianity in particular, were nullified by the adoption of the Federal Constitution. The Constitution, like the Declaration, assumes an existing moral order that was generally held to be based on “revealed law or divine law” and “the law of nature,” which William Blackstone taught in his multi-volume work Commentaries on the Laws of England was “coeval [existing at the same time] with mankind and dictated by God Himself” (1:41-142).

The Constitution did not attempt to set forth a new civil casuistry. This is why there is no legal code found in the Constitution. There are no prohibitions against murder, theft, or rape. The Constitution, like the Declaration (“the Laws of Nature and of Nature’s God”), assumes the existence of an external Higher Law.

The French Declaration of the Rights of Man did not recognize a theistic view of rights. Article 3 of the Declaration stated: “The principle of all sovereignty resides essentially in the nation. No body nor individual may exercise any authority which does not proceed directly from the nation.”

Corrupting the logic of the Declaration of Independence, the French revolutionaries declared, No nation—no rights. The French revolutionaries were self-conscious about their efforts to turn France into a secular state. Throughout the nation a “campaign to dechristianize France spread like wildfire.”1

The dechristianization of the French Republic required a substitute religion. The leaders of the Paris Commune demanded that the former metropolitan church of Notre Dame was to be reconsecrated as a “Temple of Reason.” Keith Feiling observed: “Human reason set up a cross on Calvary, human reason set up the cup of hemlock, human reason was canonized in Notre Dame.”2 Blackstone’s comments on reason are appropriate on this point:

And if our reason were always, as in our first ancestor before the transgression, clear and perfect, unruffled by passions, unclouded by prejudice, unimpaired by disease or intemperance, the task would be pleasant and easy; we should need no other guide but this. But every man now finds the contrary in his own experience; that his reason is corrupt, and his understanding full of ignorance and error” (1:42).)

On November 10, 1793, a civic festival was held in the new temple, its facade bearing the words “To Philosophy.” In Paris, the goddess Reason “was personified by an actress [who was] carried shoulder‑high into the cathedral by men dressed in Roman costumes.”3

The Commune ordered that all churches be closed and converted into poor houses and schools. “Church bells were melted down and used to cast cannons.”4

The Commune ordered that all churches be closed and converted into poor houses and schools. “Church bells were melted down and used to cast cannons.”4

Blatant infidelity precipitated that storm of pitiless fury. The National Assembly passed a resolution deliberately declaring ‘There is no God;’ vacated the throne of Deity by simple resolution, abolished the Sabbath, unfrocked her ministers of religion, turned temples of spiritual worship into places of secular business, and enthroned a vile woman as the Goddess of Reason.”5

The French Revolution replaced the God of Revelation with the Goddess of Reason, with disastrous results.

Blood literally ran in the streets as day after day “enemies of the republic” met their death under the sharp blade of Madame Guillotine. “France, in its terrific revolution, saw the violent culmination of theoretical and practical infidelity.”6

The French calendar was also changed. “At the suggestion of the deputy Romme, the Convention voted on 5 October 1793 to abolish the Christian calendar and introduce a republican calendar.”7

The founding of the Republic on September 22, 1792, was the beginning of the new era, a New Year 1. While the year still had twelve months, all were made thirty days long. “Weeks were replaced with periods of ten days (decades) so that the Christian Sunday would disappear….”8

The New Republic went beyond this by changing place names that had “reference to a Christian past…. Children were named after republican heroes such as Brutus and Cato, and observance of the new Revolutionary calendar, which abolished Sunday and Christian Feast days, was enforced.”9

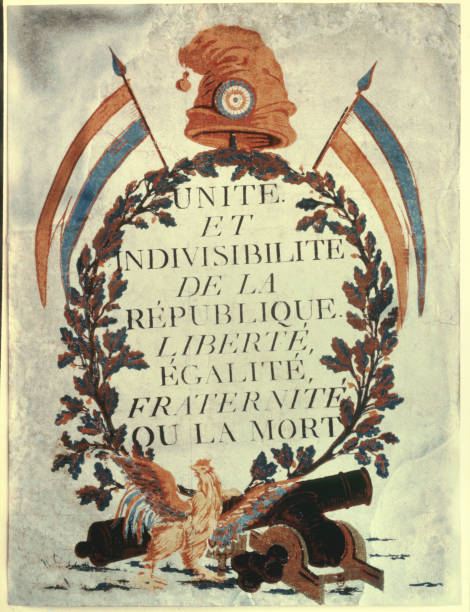

Unity, Indivisibility of the Republic, Liberty, Equality, Fraternity or Death

All the elements for a new revolution can be found in the French Revolution, everything from anti-Christian fervor and religious adherence to pure reason to the establishment of a powerful political elite intent on ruling the masses.

- Walter Grab, The French Revolution: The Beginning of Modern Democracy (London: Bracken Books, 1989), 165. [↩]

- Keith Feiling, Toryism: A Political Dialogue (London, 1913), 37-38. Quoted in Russell Kirk, The Conservative Mind: From Burke to Eliot, 5th ed. (Chicago: Regnery, 1972), 7-8. [↩]

- Francis A. Schaeffer, How Should We Then Live? (1976) in The Complete Works of Francis A. Schaeffer: A Christian Worldview, 5 vols. (Wheaton, IL: Crossway Books, 1984), 5:122. [↩]

- Grab, The French Revolution, 166. Robespierre considered the anti-Christianization campaign to be a political miscalculation. “At the beginning of December [1793], at Robespierre’s suggestion, the Convention withdrew its anti-religious measures and restored the principle of religious freedom” (166-67). [↩]

- Charles B. Galloway, Christianity and the American Commonwealth; or, The Influence of Christianity in making This Nation (Nashville, TN: Publishing House Methodist Episcopal Church, 1898), 25. [↩]

- Peck, The History of the Great Republic, 321. [↩]

- Grab, The French Revolution, 165. Also see “Marking Time: Different Ways to Count the Changing Seasons,” Did You Know? New Insight into the World that is Full of Astonishing Stories and Astounding Facts (London: Reader’s Digest, 1990), 267. [↩]

- Grab, The French Revolution, 165. [↩]

- Richard Cobb, gen. ed., Voices of the French Revolution (Topsfield, MA: Salem House Publishers, 1988), 202. Also see Simon Schama, Citizens: A Chronicle of the French Revolution (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1989), 771-780. [↩]